The Double-Slit Paradox Resolved

How a novel approach to Hugh Everett's "Many-Worlds Interpretation" pulls back the veil on quantum probability and radically alters our understanding of time and space

In 1801 Thomas Young found that by shining light through two slits at once, a wave interference pattern was produced in the light and shadow on the wall behind the openings, the same sort of interference we would expect from waves of water. This discovery became the basis of his wave theory of light, but he could not have known how much deeper the rabbit hole would go, that similar experiments would continue to puzzle scientists over two hundred years later.

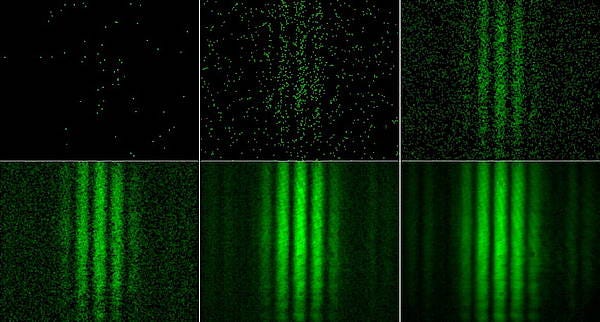

In 1927 a double-slit experiment was performed by Davisson and Germer, but instead of shining a continuous beam of light at the slits, they fired individual electrons, one after another. After passing through the openings the electrons would strike a crystalline nickel target, recording the impact with the appearance of a tiny, shining dot. It was suspected that the sum of the impacts would amount to two clusters of dots (one cluster behind each slit, as we would expect from a classic projectile), but in fact the dots gradually formed a wave interference pattern like that observed in the Young experiment. The electrons, fired one at a time, were somehow interfering with themselves like waves, then striking the back wall like point particles. The same phenomenon was observed with larger particles, atoms, and even molecules.

Subsequent experiments discovered an equally strange fact: placing a particle detector in front of one of the slits, so that one knows which slit the particle has passed through, causes the wave interference pattern to disappear. When we know which slit the particle has passed through, the impacts form two distinct clusters, much as we would expect from a classically-behaving projectile.

No one has satisfactorily explained why or how this happens.

The Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics maintains that reality is indeterministic on a quantum level. Before we detect them at a specific location, particles do not have definite positions. A wave-function defined by the Schrödinger equation determines the positions where the particle is most likely to be found, and we consider the particle’s present state a superposition of all of these possible positions until the moment when the particle is detected and the wave-function “collapses” into a single position.

This “probability wave” is not merely an abstract notion. It is real and the direct source of the wave distribution of particle impacts, but we have never had a clear way of visualizing it or comprehending it. The mathematical framework of quantum theory is widely accepted as an accurate description of atomic and sub-atomic phenomena, but in more than ninety years physicists have not been able to reach any consensus regarding the metaphysical basis of its most central mystery. Some physicists are willing to take indeterminism at face value. Others are not.

Consider a roulette wheel. It is fair to say that my success on any given throw can be modeled by probabilistic mathematics and that the possible outcomes are undetermined until the ball has settled on a number. However, it is not fair to say that probabilistic algorithms have any influence on the physical wheel. In all of nature except for quantum physics, it is generally accepted that deterministic laws underpin probabilistic outcomes. In the quantum world, some physicists sincerely believe that the laws of physics are indeterministic and that particle positions are determined on a fundamental level by probability equations.

There is only one explanation that has come close to alleviating the metaphysical woes of the probability wave: Hugh Everett III’s relative-state theory, originally called the “Theory of the Universal Wave Function” and now commonly known as the “Many-Worlds Interpretation.”

In Everett’s theory everything exists as part of a universal wave function and there is no wave-function collapse. In what we might call parallel universes, every possible particle location predicted by the wave-function is realized as a separate branch of reality. To an individual observer, a particle will appear at a single location, but meanwhile other branches of the same particle have appeared at different locations relative to other observers, who are oblivious to the fact that they are one out of an immense number of nearly identical copies. Our observations do not “collapse” the wave-function in any meaningful way; they merely reveal to us which momentary branch of the universal wave function we exist in.

This paradigm is appealing because the outcome is determined mechanically but is subjectively probabilistic. There is no need for ad hoc wave collapse. Indeterminism, rather than being a fundamental rule of the universe, arises from the subjective experience of the observer, whose seemingly-linear existence is in reality a drunken walk through a vast series of branching corridors.

Everett’s Many-Worlds Interpretation has steadily grown in popularity, but it is not universally accepted. It sounds far-fetched. It sounds like science fiction. It is our best bet for a metaphysical explanation of the double-slit experiment, but it requires us to rely upon a logical abstraction which is incomplete, unverifiable, and difficult to reconcile with our prevailing conception of space-time.

Where are these parallel universes? How do they fit into the four dimensions asserted by General Relativity? How does the wave interference pattern emerge between parallel universes, and why does it disappear when we detect the energy passing through the slits? If we could answer these questions, we would solidify the case for Everett’s theory and finally put the debate to rest.

Let’s give it a try…

According to General Relativity, reality is four-dimensional, consisting of three dimensions of space and one dimension of time. In an upcoming article, I will make the case that reality is indeed four-dimensional, but that time should be considered dimensionless and the four dimensions are all spatial. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves, however. For now, I only mean to convince you that there is a fourth dimension, and it’s easier to conceptualize than you might be thinking.

Where are the parallel universes? This question is perhaps the biggest impediment to the MWI’s acceptance. We are asked to believe in something we cannot see and which we have little capacity to visualize. There is a tendency to imagine a parallel universe as being just really, really far away, as if our universe is a big bubble, and just outside of that enormous bubble is another, similar bubble, and so on to infinity. Indeed, most pop culture representations of Everett’s theory take a similar approach:

These representations are absolute nonsense. If there is a fourth dimension, then “parallel universes” do not need to be unimaginably far away. They can be stacked right on top of us, with the x,y,z positions of one branch superimposed almost exactly on top of the x,y,z positions of another.

In order to properly imagine our relationship with a fourth dimension, it helps to scale things down and imagine how a two-dimensional reality can relate to a third dimension.

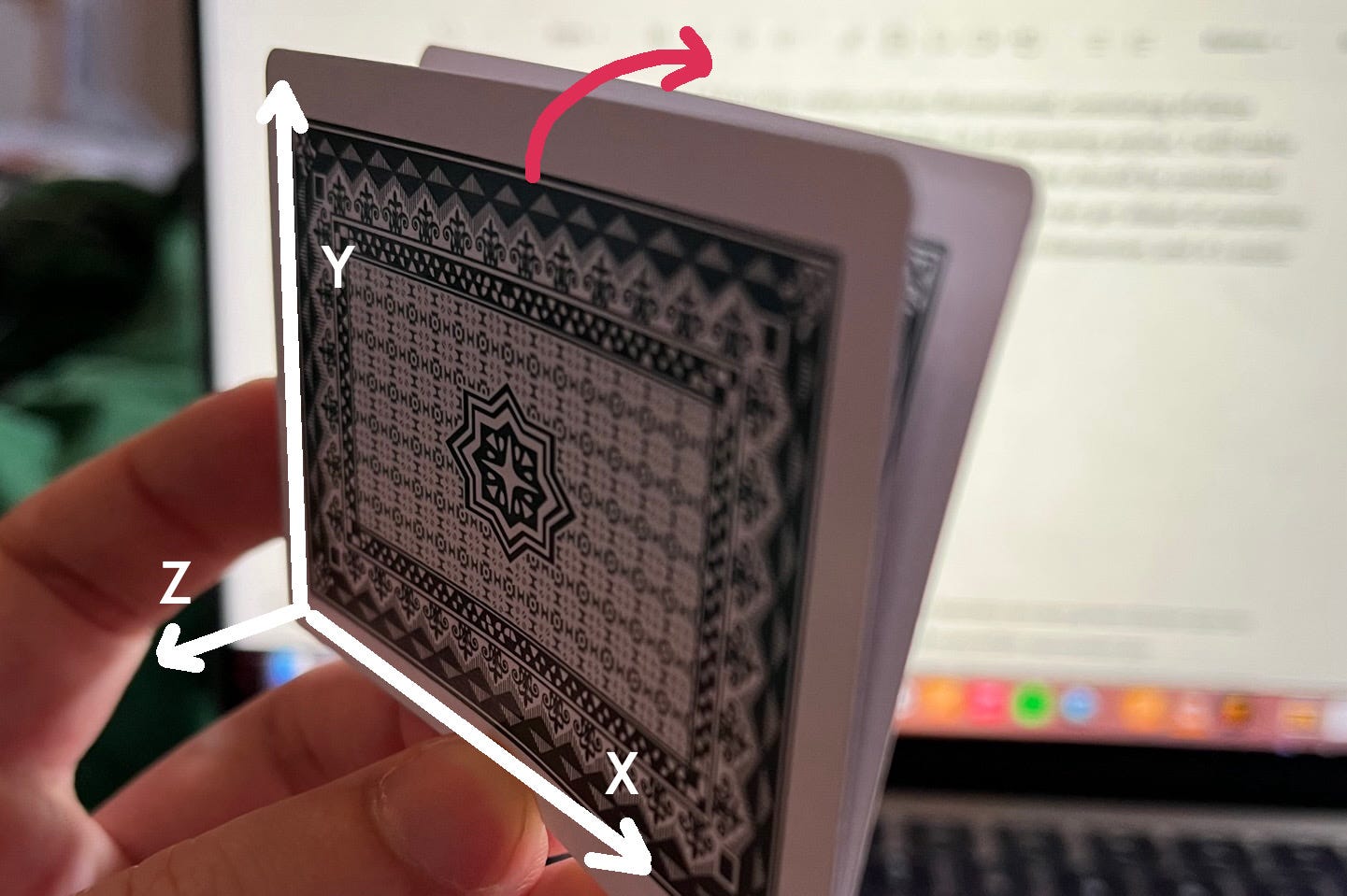

Consider this playing card a two dimensional universe. If we rotate it slightly into the third dimension, along the x axis….

…We find two identical universes that are in direct contact with each other and very nearly superimposed. We could stack cards around a full 360 degrees. The more cards, the closer they are packed together, and the closer they are packed together, the more perfectly one neighbor is superimposed upon the next. The important thing to note is that they are all touching. They are occupying the same x and y space, but they are invisible to each other because of a tiny translation in a third dimension.

In the image above, I arbitrarily chose to rotate along the x-axis, meaning that each x point would remain the same in each parallel universe, while the y and z points would change incrementally with the rotation. I could just as easily chose to rotate around the y-axis, and have the x points incrementally changing with z.

Applying a 4th dimension to a 3-dimensional reality allows us three different ways of rotating the space into the higher dimension. Let’s call this dimension the imaginary dimension and represent it with imaginary numbers, like we did in my previous article on Euler’s Formula. By translating x, y, or z ever-so-slightly into the i dimension, I create a parallel space which is in direct contact with the original space, still sharing two of its original Cartesian coordinates and only infinitesimally displaced in the third.

Thus, we do not have to look very far to find our nearest parallel selves. They are superimposed on top of us, occupying the same three dimensional space.

The “parallel universes” (in quotes because from a higher perspective it’s all the same universe) are slightly out of phase with us in the fourth dimension, but they are, in a very literal sense, overlapping us. Rather than the series of bubbles from the goofy images above, we should imagine thoses bubbles all in essentially the same location, rotated slightly out of phase with each other in the 4th dimension.

With this constant superposition, it becomes much easier to understand how one universe might interfere with another on a quantum level. But we still need to explain the results of the Double-slit experiment. How does the wave interference pattern appear particle by particle? And why does it disappear when we know which slit a particle is passing through?

The answer to the first question is fairly obvious from our explanation of the 4th dimension. When we say that a point particle interferes with itself, we are not being precisely accurate. The particle is really one sliver of a wave which is continuous across a rotation in the 4th dimension or, put another way, continuous across many, many parallel branches which are in either direct contact with each other or extremely close proximity with each other. The interference is not between the “particle itself” but between the particle and the indefinite number of copies of itself, which are very nearly superimposed.

When we fire this “individual particle” at the double-slit and the wall behind it, we are really sending a four-dimensional wave.

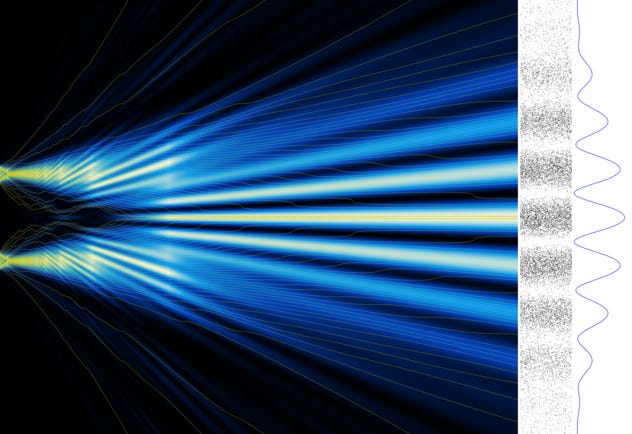

In the photo below, we have a representation of the double-slit experiment, with many particle trajectories adding up to a wave-interference pattern after countless tests. However, we could just as easily imagine this image as representing a single test, a single particle launch, but seen from the fourth dimension. In our limited, three-dimensional perspective, we see only one of the impact points, but all of them exist in nearby branches of space-time.

Now for the trickier question: Why does the wave-interference pattern disappear when we place a particle detector at one of the slits?

The short answer is divergence. The activation of the particle detector does not “collapse” the wave-function, it complicates it. It creates two separate branches of reality, one in which the detector is activated and one in which it is not. Every version of the particle which has passed through the right side will continue interfering amongst themselves. Every version which has passed through the left side will continue interfering amongst themselves. But the two sets, right and left, have been divided by the interaction with the detector into two separate relative states. Both sets continue to exist, but they no longer exist in the near-perfect superposition necessary to generate a visible interference. When we see the point of light from the particle impact, it is still one part of a larger wave and a wave-interference pattern, but a wave interference between only those versions of the particle which passed through the same door and remain in the same relative state, the same branch of reality.

I’ll try to explain it visually, using another one of my shitty graphs.

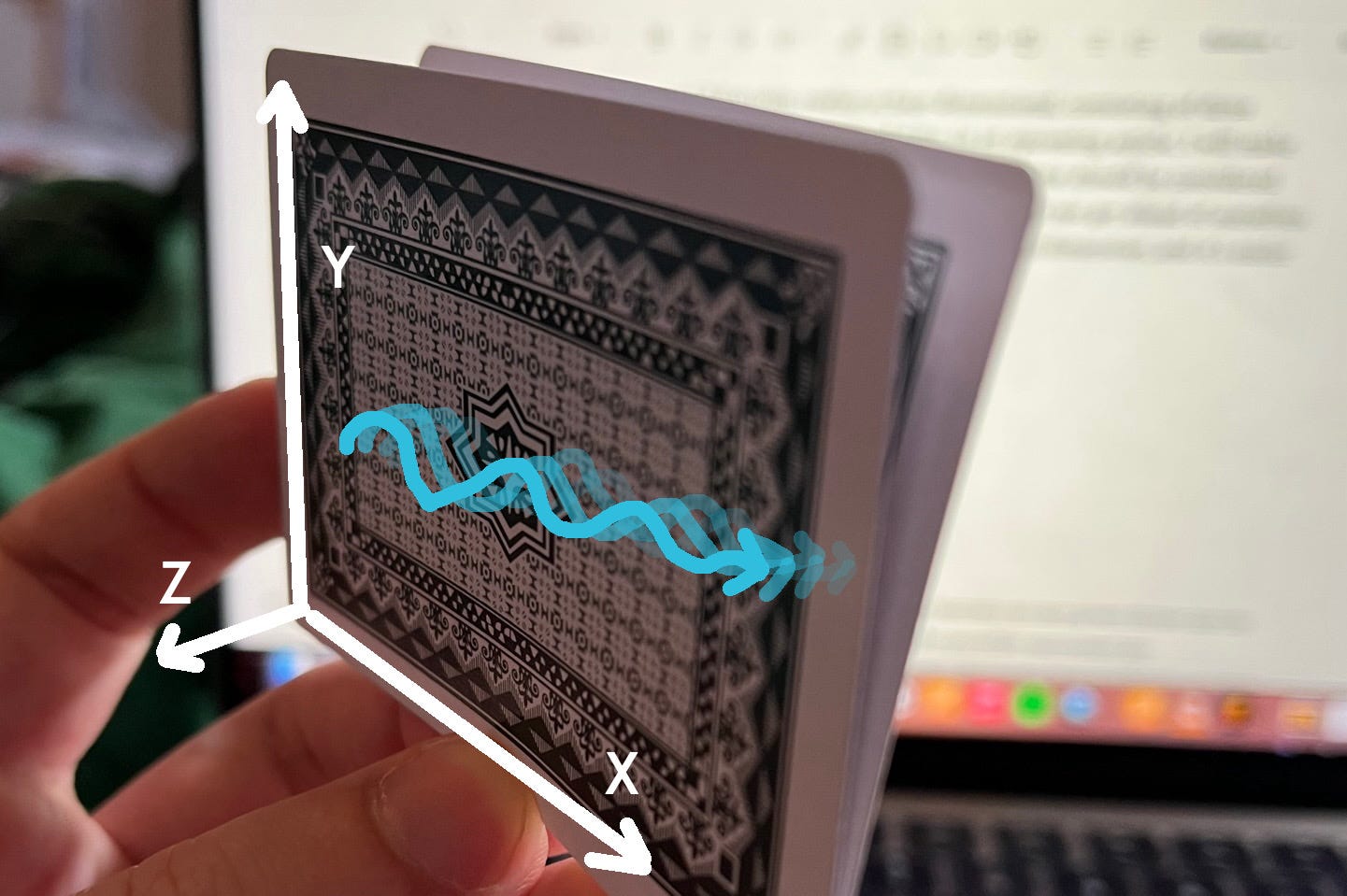

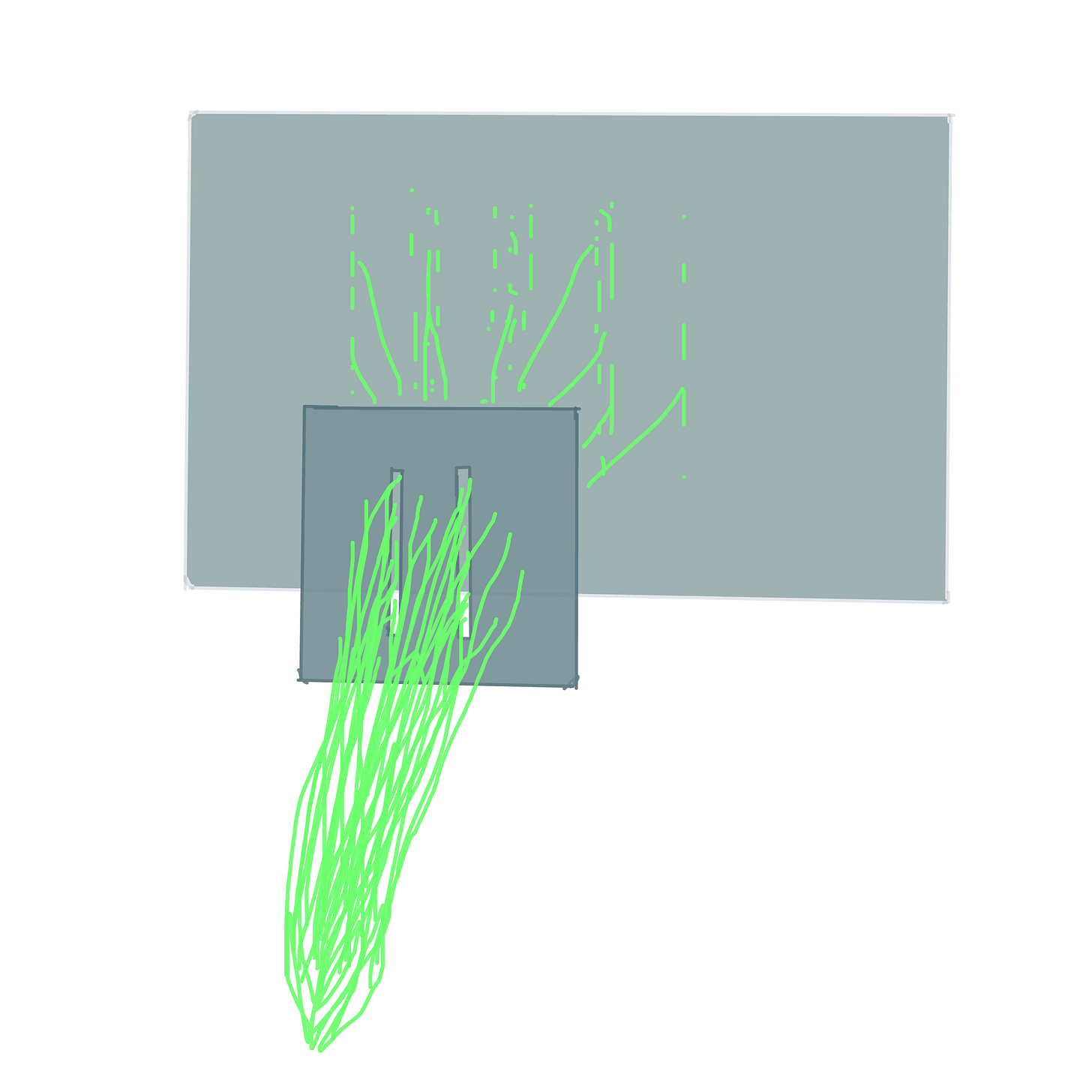

Here’s one test (one particle launch) with no detectors:

All of the possible particle trajectories continuously interfere with another, from one end of the border to the other, until the wave strikes the wall and we see one result out of many.

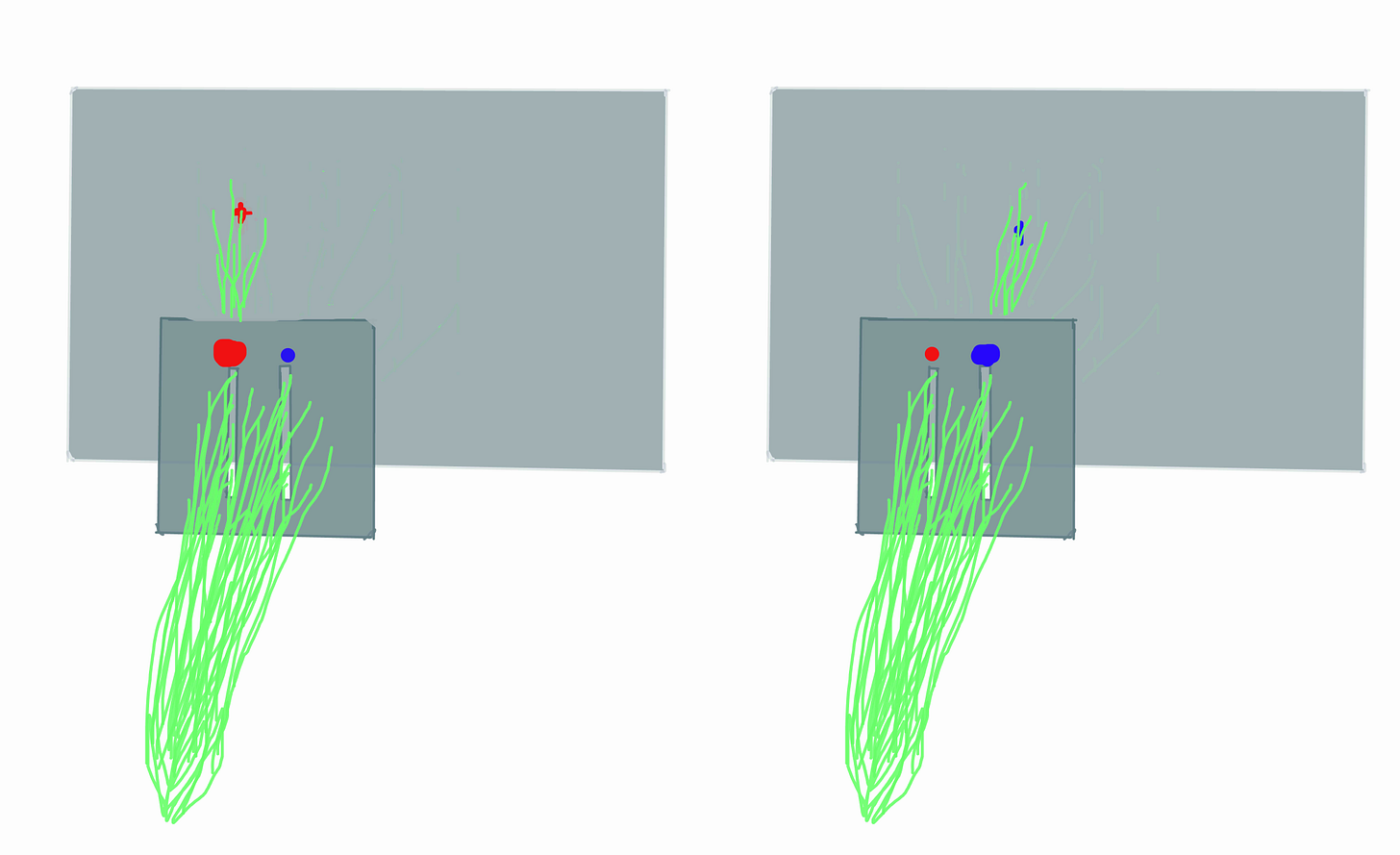

With a detector, the two paths branch apart due to the detection. Reality bifurcates:

Repeat this above test a few hundred times, and you get a cluster on the right and a cluster on the left.

A similar result cannot be obtained without bifurcation of the two sets. A physical interaction with the detector could arguably cause one side to become out of phase with the other and dampen the interference or alter the interference pattern without a large-scale bifurcation, but it would not make the interference disappear completely.

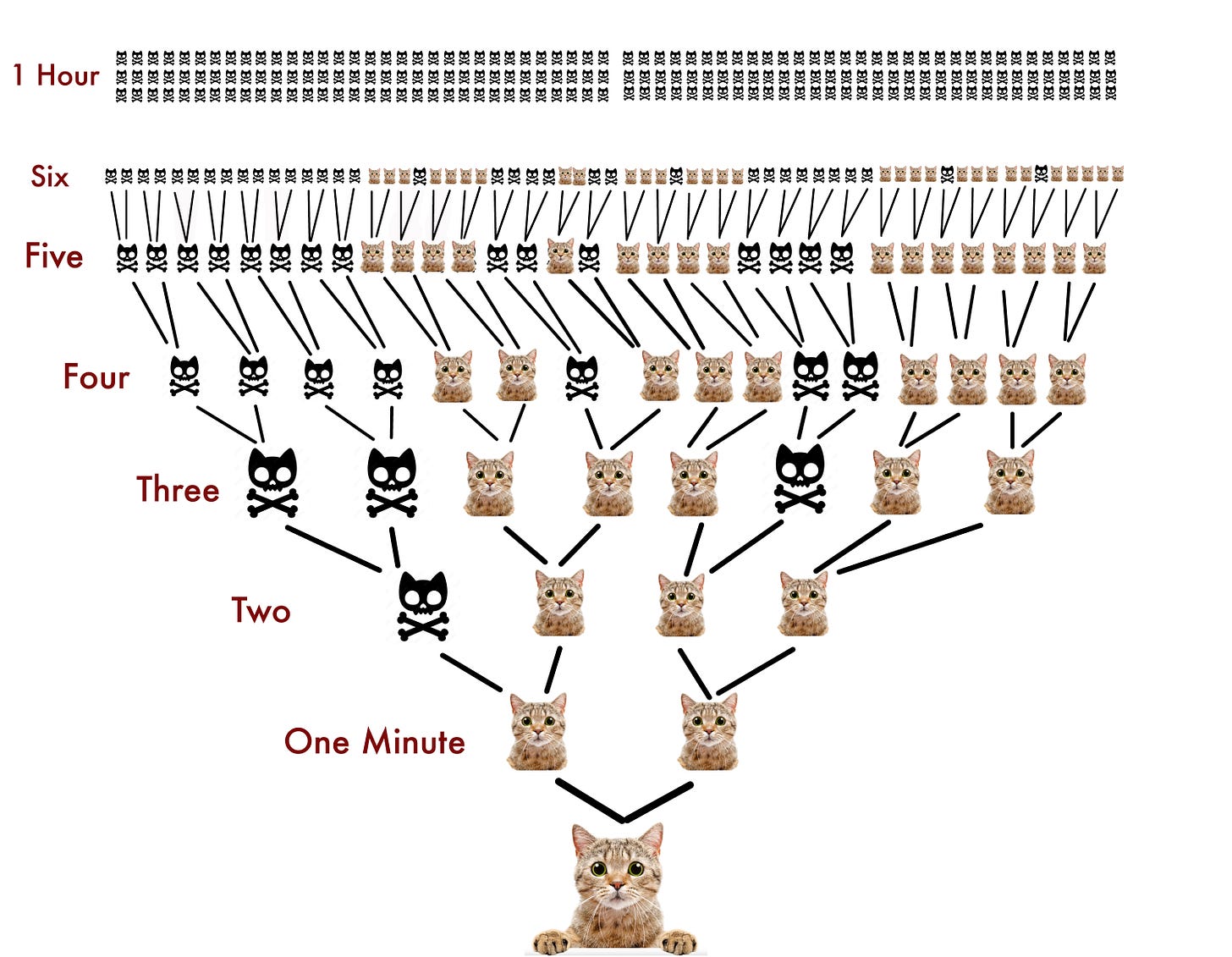

Now, what does this mean for Schrödinger’s Cat? We could say that, yes, the cat is both alive and dead, but not within our own box. If I open the box after six minutes and find the cat has been dead for five minutes, then I am occupying a branch of time in which he has been definitely, unequivocally dead for five minutes. There are branches of time in which he is still alive, but they diverged from me five minutes ago.

Albert Einstein famously rejected the notion that God “plays dice with the universe.” Edwin Schrödinger, who wrote the most essential equation of quantum mechanics, similarly resisted the philosophical stance of his fellow physicists. In Schrödinger’s opinion, the notion of an observer “collapsing” the superposition of cat states was silly. He pointed out that there was nothing in the math, and nothing in his wave equation, that suggested a collapse. He wrote that it was “patently absurd” that the wave-function should “be controlled in two entirely different ways, at times by the wave equation, but occasionally by direct interference of the observer, not controlled by the wave equation.” Everett’s Many World’s Interpretation allows us to visualize a solution to quantum mechanics in which God does not play dice with the universe, but the universe plays dice with us. Everything unfolds according to deterministic laws, but our perspective is subjectively indeterminate, the result of an infinite series of roulette spins, in which every number hits, and we see only one result.

The only question which remains is in the exact nature of reality’s bifurcation. Does a local divergence imply the divergence of the entire universe? If an electron in a distant galaxy is confronted with a choice of two quantum paths, does this cause the entire Universe, including ourselves, to split? And if so, to what extent is the splitting synchronous or arhythmic? Does time evolve by discreet moments, in which each moment entails a spltting?

Only time will tell.